This page explains how to use ScriptableObjects as logic containers. By doing this, you can treat them as delegate objects, or little bundles of actions that you can call when needed.

This is the fourth in a series of six mini-guides created to assist Unity developers with the demo that accompanies the e-book, Create modular game architecture in Unity with ScriptableObjects.

The demo is inspired by classic ball and paddle arcade game mechanics, and shows how ScriptableObjects can help you create components that are testable, scalable, and designer-friendly.

Together, the e-book, demo project, and these mini-guides provide best practices for using programming design patterns with the ScriptableObject class in your Unity project. These tips can help you simplify your code, reduce memory usage, and promote code reusability.

This series includes the following articles:

Before you dive into the ScriptableObject demo project and this series of mini-guides, remember that, at their core, design patterns are just ideas. They won’t apply to every situation. These techniques can help you learn new ways to work with Unity and ScriptableObjects.

Each pattern has pros and cons. Choose only the ones that meaningfully benefit your specific project. Do your designers rely heavily on the Unity Editor? A ScriptableObject-based pattern could be a good choice to help them collaborate with your developers.

Ultimately, the best code architecture is the one that fits your project and team.

Using the strategy pattern, you can define an interface or base ScriptableObject class and then make those delegate objects interchangeable at runtime.

One application is to encapsulate algorithms for doing specific tasks into a ScriptableObject and then use that ScriptableObject in context of something else.

For example, if you were writing an AI or pathfinding system for an EnemyUnit class, you might create a ScriptableObject with a path search technique (like A*, Dijkstra, etc.).

The EnemyUnit itself wouldn’t actually contain any pathfinding logic. Instead, it would keep a reference to a separate “strategy” ScriptableObject. The upshot of this design is that you can swap to a different algorithm simply by exchanging objects. This is one way to choose different behaviors at runtime.

When the MonoBehaviour needs to perform a task, it calls the external methods on the ScriptableObject rather than its own. For example, the ScriptableObject might contain public methods for MoveUnit or SetTarget for driving the enemy unit and specifying a destination.

You can improve this pattern with an abstract base class or an interface. Doing that means any ScriptableObject that implements the strategy can be swapped with another. This hot-swappable ScriptableObject “plugs” into the MonoBehaviour referencing it – even on the fly at runtime.

If you need the EnemyUnit to change behaviors because of game conditions, the outer context (the MonoBehaviour) can check for those conditions. Then, it can plug in a different ScriptableObject as a response.

By separating implementation details into a ScriptableObject, you can also facilitate a better division of responsibilities amongst your team. One developer could focus on the algorithm inside the ScriptableObject, while another works on the MonoBehaviour context.

To create this pluggable behavior, make sure to:

Organizing your code like this can make it easier to switch between different implementations of the same strategy. This pluggable behavior then becomes easier to debug and maintain.

An algorithm or strategy doesn’t have to be complicated. The PaddleBallSO project, for example, demonstrates a fairly basic audio playback system in the SimpleAudioDelegate.

The abstract class, AudioDelegateSO, defines a single Play method that accepts an AudioSource parameter. The concrete implementation then overrides this.

The SimpleAudioDelegateSO subclass defines an array of AudioClips. It chooses a random clip and plays it back using the overridden Play method implementation. This adds a variation in pitch and volume within a custom range.

Though it’s a just a few lines, you can make many different audio effects with the code snippet below.

While this specific example isn’t really suitable for heavy audio use, it’s presented here as a basic usage demo of ScriptableObjects in a strategy pattern.

A designer can create many different ScriptableObjects to represent sound effects without touching the code. Again, this requires minimal support from a developer once the base ScriptableObject is complete.

In PaddleBallSO, anyone can now set up a new array of sounds to play back when the ball strikes one of the level walls. Designers gain creative independence and flexibility because they are working entirely in the Editor. This approach frees up programming resources, since developers no longer need to assist with every design decision.

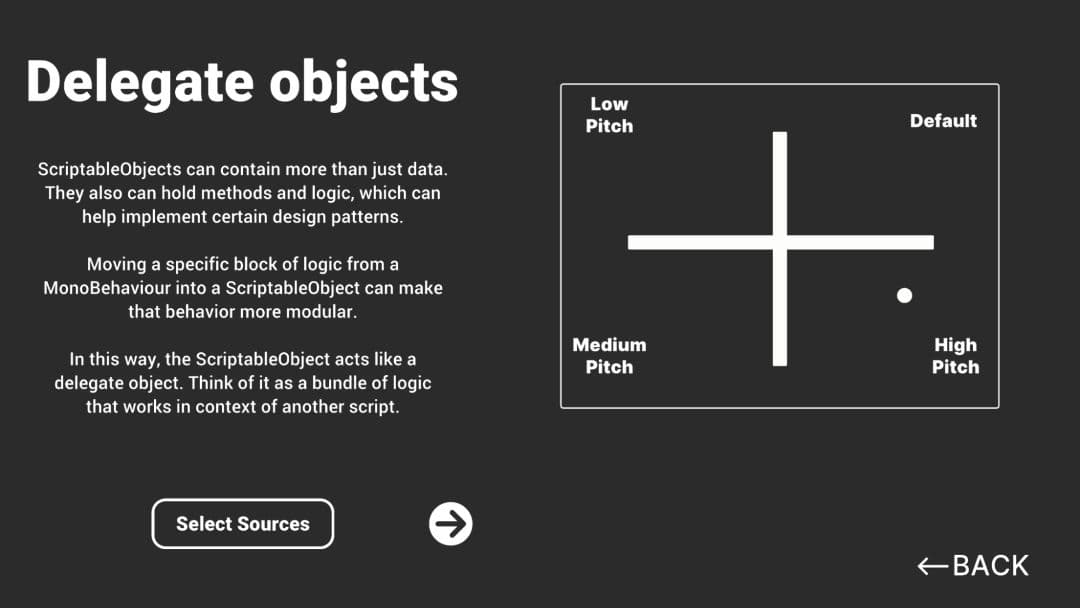

You can also see the audio example in the Patterns demo. Each sound derives from a slightly different SimpleAudioDelegateSO asset, with small variations between instances.

In this example, each corner includes an AudioSource. A custom AudioModifier MonoBehaviour uses a ScriptableObject-based delegate to play back sound.

The differences in pitch stem only from the settings on each ScriptableObject asset (BeepHighPitched_SO, BeepLowPitched_SO, etc.).

Using a ScriptableObject to control the action logic can make it easier for your design team to experiment with ideas. This enables a designer to work more independently from a developer.

The PaddleBallSO project also uses the strategy pattern in its objective system. Though this isn’t something that needs to vary at runtime, encapsulating each object in a ScriptableObject provides a flexible way to test win-lose conditions.

The abstract base class, ObjectiveSO, holds values like the objective’s name and whether it has been completed.

The concrete subclasses, like ScoreObjectiveSO, then implement the actual logic on how to complete each objective. They do that by overriding the ObjectiveSO’s CompleteObjective method and adding the win condition logic.

Does the player need to attain a specific score or defeat a certain number of enemies? Do they need to reach a specific location or pick up a specific item? These are common win conditions that could become ScriptableObject-based objectives.

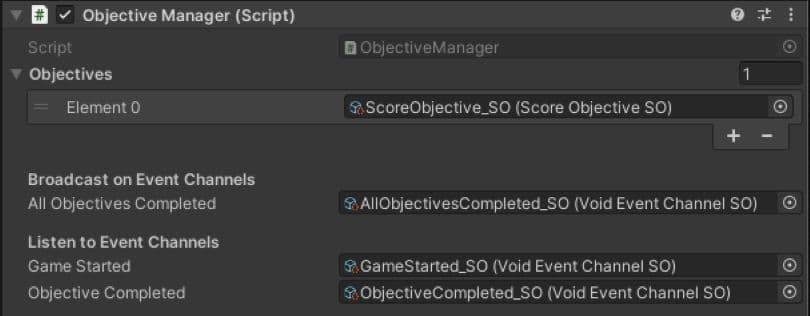

The ObjectiveManager serves as the larger context for the ScriptableObjects. It maintains a list of ObjectiveSOs and relies on each ScriptableObject to determine if it’s complete. When every ObjectiveSO shows a state of completion, the game is over.

For example, the ScoreObjectiveSO shows one way to implement a scoring objective:

The ObjectiveManager only cares that all of the given objectives are complete. It’s unaware of details within each objective itself.

Again, the goal here is modularity. This lets you customize each ObjectiveSO without affecting pre-existing ones.

The PaddleBallSO game really only has one objective. If one of the players reaches the winning score goal, gameplay ends.

However, you could extend this or combine objectives to create a more complex objective system. Experiment and see if you can build new game modes (e.g., score a minimum number of points before time runs out).

Since the logic is encapsulated inside a ScriptableObject, you can swap any ObjectiveSO for another. Making a new win condition simply involves reconfiguring the list in the ObjectiveManager. In a sense, the objective is “pluggable” into the surrounding context.

Note that one handy aspect of the ObjectiveSO is the event used to send messages between GameObjects. Next, we’ll explore how to use ScriptableObjects to implement this event-driven architecture.

Read more about design patterns with ScriptableObjects in the e-book Create modular game architecture in Unity with ScriptableObjects. You can also find out more about common Unity development design patterns in Level up your code with game programming patterns.